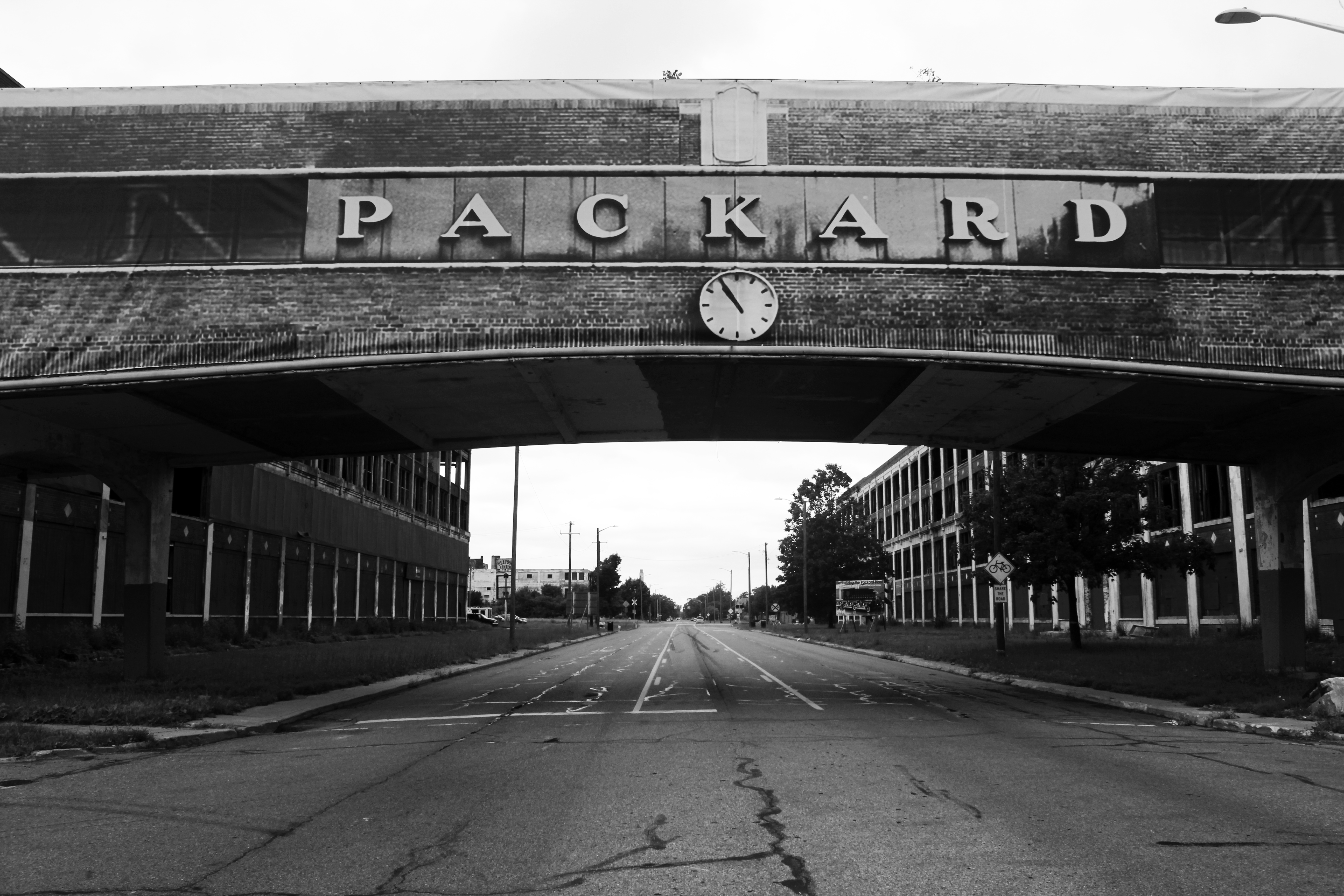

Scott Sines, ©The Green Rocket News

The problems in Line 6B were known for years before the spill.

An investigation by the National Transportation Safety Board confirms that Enbridge knew, in 2005, of the cracks in Line 6B that eventually split open. A 2005 Enbridge engineering assessment reported, “… six crack-like defects ranging in length from 9.3 to 51.6 inches were left in the pipeline, unrepaired, until the July 2010 rupture.”

They were not repaired because they didn’t fit the profile of a looming leak. “Records show that prior inspections in 2005, 2007 and 2009 identified at that location a defect, but the defect in their judgment had not yet reached the repair criteria that PHMSA … established in Federal regulation,” Rep. James Oberstar, chairman, Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure said during congressional hearings.

In 2008, inspection results of Line 6B showed 140 “anomalies” in the pipeline requiring repair within 180 days, 26 were repaired. In 2009, another inspection identified 250 “anomalies”, 35 were repaired. Leaving 329 defects unrepaired, Enbridge reduced the pressure in the pipeline to eighty percent for one year, while deciding whether to repair or replace the pipeline.

July 15, 2010, was a busy day for Enbridge in D.C.

On the same day the company was asking the PHMSA for another two and a half years to study the repair or replace decision on Line 6B, Richard Adams

Ten days later, Adams’s own staff made a fool out of him. On Sunday, July 25, 2010, at 5:58 p.m. EST, Line 6B burst. For seventeen hours the pipeline gushed oil into a wetland that fed Talmadge Creek, which dumps into the Kalamazoo River.

The investigation revealed that the control room actually made the problem worse. “During the time lapse, Enbridge twice pumped additional oil (81 percent of the total release) into Line 6B during two startups; the total release was estimated to be 843,444 gallons of crude oil.”

EPA estimates about 180,000 gallons of Line 6B oil remain on the river bottom. According to an EPA report the company can recover an additional 12-18,000 gallons of oil through dredging. The rest of the oil will be monitored “over time.”